Sweet Intuition

Stories similar to this that you might like too.

The next morning, the first thing I did was to get a phone message from my sister-in-law: “I’m sorry you couldn’t make it out for Christmas. But we’ll see you soon.” My wife and I had both been looking forward to going home on break, but with everything that happened last night—with all those men who tried to kill me—there’d be no way.

The only thing I could think about was getting back here and finding my father, so he wouldn’t do anything else crazy or dangerous. There was a good chance this whole thing had just been an attempt at robbery gone bad, but if not…

I thought about calling the police in New York and telling them what happened. But after what happened yesterday, they were probably already pretty freaked out, too. And I knew there’d be questions, and I didn’t know if they’d want me to stay in town while they figured out whatever it was that was going down.

Or maybe I should call a few of my friends and have them drive out and meet us up here? If something did happen again, maybe someone would be able to help me find my father. And then maybe he wouldn’t be able to hurt anyone else, or himself. It made sense, right?

But as I thought about all these things, sitting around in bed trying to decide how best to proceed, I realized that one of the reasons we hadn’t gone home for Christmas was that none of us really liked being around our family.

We’d always gotten along okay when we were together over Thanksgiving break or spring break. But we never spent much time together during the school year, because we lived far away. Plus, with my father’s issues, I wasn’t sure we wanted him anywhere near our house.

It took some serious effort on my part to stop worrying about the past. So instead of calling anybody, I decided to go out onto campus and try to figure out what this business was all about. If nothing else, the more research I could do, the less likely I’d be to forget anything important later on.

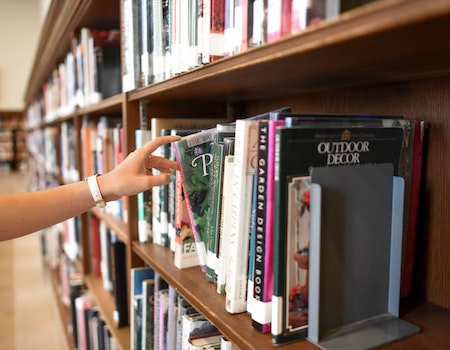

I left the dorm and headed for the library. As I walked by the student union building, I noticed a group of guys hanging around outside, smoking cigarettes and staring at me. One of them pointed at me like he recognized me, but before I could say hi, I hurried into the library, where I found one of the study tables near a window and pulled out my laptop.

I sat there for several hours, typing up what I remembered of yesterday, trying to remember every detail, from the feel of his fingers squeezing my throat to the taste of blood in my mouth. Every moment, even the ones I didn’t really understand why I was paying attention to, was crucial. If I forgot something, it might cost someone else their life.

As I worked, I heard a couple of people come inside. First, one guy came in and got coffee, and then another. A while later, they started playing pool and drinking beer. At least four or five other students stopped in throughout the day, most of them coming through the glass doors from outside.

The place became packed and loud enough that I was eventually forced to turn off my computer and focus on reading books. Eventually, I ended up staying until closing time, and as I went through the lobby on my way out, I saw two of the older gentlemen who had tried to mug me earlier in the week.

They stood behind a long counter at the entrance to the library, selling books and magazines.

“Hello,” said a woman walking toward them. Her voice carried well across the room, and she spoke so loud that everyone in the lobby turned and looked at her. It didn’t take me very much effort to pick out the woman who was asking about me: Missy.

She walked toward the old men, looking right at me, smiling, waving. It was weird how fast things like this happened sometimes. You can’t predict how your day is going to unfold.

Missy seemed to be talking about me for a while, making small talk. The three guys standing there, waiting on customers, nodded politely. But I wasn’t listening to any of it. My head was full of thoughts about my father, trying to remember everything he ever told me, to figure out what was important.

But Missy finally finished speaking and smiled at the men and started moving farther into the building. Then one of the guys called my name, just loud enough for me to hear. He asked if I needed him for anything today. His face was dark with stubble, and his hair was cropped short. I looked away from him and stared at Missy. She moved past the front desk to start helping customers.

She’d seen me. Maybe I wasn’t invisible after all.

***

The next morning, I drove down to the diner and took one of the booths. It was early yet, and the place was mostly empty. When I ordered breakfast, the waitress brought me a cup of coffee with an extra shot, and then a little while later I spotted Missy coming through the door.

She waved as she passed by the table toward the kitchen, her hair still wet from a shower, wearing jeans and a t-shirt. After she disappeared around the corner, I reached under my jacket and pulled out my pistol, and put it back in its holster.

After a few minutes, Missy reappeared in the doorway and walked to my booth.

“Hi,” she said, smiling. “You look tired. Did you get much sleep?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Just a couple of hours.”

She shrugged.

I knew better than to mention my dad’s problems to anyone. I also didn’t know who Missy was, except that she used to work at the college library. What had happened last night? Had she somehow known I was there?

Or had she overheard the commotion when the guy grabbed me and threw a bunch of books on top of us? It would be strange for her not to have realized what was happening.

Either way, it hadn’t been easy on me. I kept trying to tell myself that she couldn’t possibly suspect me of being involved, but if there was one thing that I had learned over the years, it was never to trust anybody. Especially girls.

Missy leaned across the table. She smelled good, like soap and shampoo. “How did you find me?” she said in a low voice. “Last time we met in a bookstore … and now here at the diner.”

“It shouldn’t be hard for someone to track a car,” I answered.

She shook her head. “No. That’s not what I’m saying at all.”

I hesitated. Something in her manner gave me pause and made me feel awkward. I didn’t want to say something stupid. Missy leaned closer again. I didn’t want to be rude or hurt her feelings. But something about her eyes, and the look in them, made me nervous.

She leaned forward even more, and I felt uncomfortable sitting so close to her. And I really didn’t need another person to know where I lived.

“Do you think my parents will go to prison?” she whispered. “Will they send me away?”

My hand tightened on the pistol handle as I considered the answer. If the police were going to believe a girl, then maybe my mother should be telling them something. But Missy was too young, and she wouldn’t understand why the detectives had to question her parents so closely.

And even if she did understand, it was unlikely that she could convince any investigators that she knew anything about my father’s business dealings.

And it would only get worse once people found out she knew me. People like Mr. Fong.

I thought long and hard before answering.

“Maybe,” I said softly.

She nodded slightly, and her lips curled up into a smile. “Okay,” she said, putting her hands on the table. “Thanks for letting me know.” She paused for a second. “What are you doing here anyway? Why haven’t you left town already?”

“I’ve got some friends living in Seattle. We’re working on a case together.”

Her eyebrows went up, and her mouth quirked into a smile. “Well, I hope your friend has the cash,” she said. Then she stood up abruptly and turned to leave. She stopped at the door and looked back at me. “We’ll speak again some time. Just promise me …” she trailed off. She bit her lip, her gaze turning uncertain.

“… to keep safe,” I finished.

When she was gone, I took a sip of my coffee and tried to relax against the seat. The place seemed quiet enough. There wasn’t a lot of foot traffic, though it was still early. And I didn’t hear voices drifting from the kitchen, nor did I see Missy anywhere among the staff.

A few moments later, I heard a man’s footsteps coming toward my booth.

“Is this seat taken?” he asked, smiling when he came around the corner. He looked a little older than Missy, his beard gray with streaks of brown, and a hint of wrinkles around his eyes.

The waitress must have seen him first because she immediately started moving toward the other end of the counter. “Uh,” I said, standing up, “it’s no problem if you can just wait a minute.”

Mr. Fong glanced at me briefly and then at the empty chair. “No, that’s okay,” he said. “But I don’t mean to impose. I can take a seat somewhere else.”

“I’d rather you stay,” I said. “If you could sit here, then I wouldn’t be bothering anyone.”

He smiled, shaking his head gently. “I think it’s fine if I do,” he said, settling in the seat next to mine. After he pulled out the chair, I noticed that his shoes were dirty and scuffed, probably worn out because of all the walking he had done since he left home this morning.

The waitress brought our drinks and put them in front of us without looking up. She seemed a little annoyed by having to serve two customers, although Mr. Fong had been paying for breakfast. “Sorry about that,” she muttered. “Some people have no respect.” She rolled her eyes and walked away.

“Don’t worry about her,” Mr. Fong said. “You know how she is.”

“She doesn’t seem very happy,” I said. It surprised me that she might be jealous of Missy and me. But it wasn’t too difficult to guess why. As a waitress, Missy was making more money than any waitress at this diner.

Not that it mattered much to me right now, but I wondered whether Missy had ever talked with the waitress about it, and what the girl thought of me being such an important player in Missy’s life.

Mr. Fong nodded and shrugged. “Oh, sure, she complains sometimes,” he said. “It’s nothing unusual for her.”

After a moment of silence, Mr. Fong sighed heavily. His face fell slightly, and he looked down at his hands resting on the table. They weren’t clean either, which bothered me more than the fact that he wore dirty shoes.

I hadn’t realized until just then that there was a faint smell of stale sweat coming from his clothes, and the hair under his arms was damp. “My mother … she died last night,” he said finally. “She passed peacefully in her sleep.”

I blinked, surprised that someone who lived outside a major city like New York or Los Angeles would have a chance to meet his relatives so often.

“I’m sorry to hear that,” I said, trying not to let my voice tremble. “How old was she?”

He shrugged. “Forty-five.” He glanced around at the empty tables and then turned his attention to me. “Do you mind if I ask you something personal?” he said quietly. “Something private.”

I hesitated. I knew how this could go: I’d be asked to reveal something about myself, and we’d start talking about our childhoods, and before long I might discover a connection between us and realize that he was a murderer.

If the police wanted me to find out anything about him, they’d be able to figure it out pretty easily once I revealed my relationship with Missy. But then again, I also knew that as a PI, I should get to know every potential witness. Maybe he could provide valuable information, maybe not; I’d never know until I asked.

So I decided to try it out and see what happened.

“I’ll tell you if you want to know,” I said. “But don’t worry, I won’t hold back.”

He smiled. “It’s okay, really. No secrets from friends,” he said. “And I think we’re going to be friends soon.”

I couldn’t help but laugh softly. “Well, good,” I said, taking a sip of coffee. “Then you can answer these questions.”

He nodded. “Okay. You look kind of young to be a PI,” he said. “Are you sure it’s legal? What’s your age, anyway?”

I laughed and took another sip. “You know better than to ask a lady her age,” I said. “And I’m thirty-two years old.”

“Thirty-two! Oh, that’s not bad,” he said. “Not too far from where I am, I guess.”

“Yes,” I said, smiling. “I’m getting older, like everybody else.”

We both sipped our coffees for a few moments before saying anything else. The waitress came back and refilled Mr. Fong’s mug.

“You know,” he said after she had gone away, “we didn’t have this kind of coffee when I was growing up. My father used to drink instant coffee instead of brewed stuff.” He laughed. “He’d make it himself, but it tasted terrible even when it was fresh.”

“Your dad made coffee?” I asked, intrigued by the idea.

Mr. Fong nodded. “Yeah, he worked at a restaurant. They had a big machine in the kitchen. Every morning he’d make enough coffee to last them all day.”

As I listened, a strange feeling began building inside me—a mix of nostalgia and sadness. For the first time since I’d known Mr. Fong, his mannerisms were becoming familiar; I felt comfortable in his presence, and the thought of leaving was beginning to bother me.

I wished it would rain, but I wasn’t sure if the weather was responsible for the strange emotions I was experiencing, or simply because I was in a foreign country and unfamiliar with its customs.

“What did he do?” I asked him. “Work in the kitchen? Or as a cook?”

“He was the owner,” Mr. Fong said and took another sip of his coffee. Then, suddenly, he stopped drinking it.

I tried to stop myself from laughing when I saw how quickly his hand had jumped up to his mouth, and for a moment thought maybe he’d swallowed it accidentally. But it wasn’t a joke, and as I watched him swallow hard and take a deep breath, I began to feel uneasy.

“Oh dear God …” he whispered, and I looked into his eyes, searching for some sign that the coffee had poisoned him, but I couldn’t find any indication that he might be hurt or sick. It was almost like watching someone die, except that no signs of pain or fear were showing on Mr. Fong’s face.

And although I’d never witnessed a person dying before, there was something about the way he stared at me that made me believe he was staring at death.

The door to the cafe opened, and a group of students came through, chatting loudly and laughing as they went to grab an afternoon snack. They seemed completely oblivious to the fact that they were walking past the dead man who was still lying on the ground with his eyes wide open, staring straight ahead.

A couple of them walked over to the counter and ordered food while others kept walking toward their table, talking and laughing as they went. Only one of them paused in front of Mr. Fong’s corpse. He bent down and checked to see if he was breathing, then shook his head and started walking away.

I followed, my curiosity piqued, wondering if there was something about him that was going to cause him trouble later on.

I found him at the end of the line outside the bathroom, talking with two other guys. One was wearing a black jacket and a pair of jeans, and the other wore a red sweater with a long gray coat over top, along with a pair of faded blue jeans. Both men carried briefcases with their textbooks and notebooks stuffed inside, ready for class.

After the three of them finished talking, they each walked off separately in different directions: the guy in the black jacket turned left and headed for the library, the guy in the red sweater went right, and the other guy went left, disappearing out of sight.

The End